The (CanL)It Crowd with Salma Hussain

Somebody said something to me recently that made me feel like my bookish joy—one of the precious sources of unrepentant happiness in my life—was insincere. It was implied that people like me only support other writers because we want to be supported in return. Who said this and when is not important. What is important, to me, is how quickly I wanted to fold into myself and hide. How I felt that I had something shameful to conceal. I wondered if this person was right, because most of my life, I have assumed the bad things people say about me are right.

A therapist told me this reaction can be a trauma response. It can be a result of low self-esteem. It can be both.

Since you are not my therapist, I’ll spare you the cataloging of past experiences that could have led to such self-doubt (if you’ve read my memoir Fuse, you know of many of them anyway). I will say, though, that when I thought about what this person said and then dug deep, and then dug deeper still, and when I cast my mind back to the pre-digital age, before I had any audience who deigned to listen to me talk about books I loved, I was still always talking about books I loved. Then, when I finally got on social media and only my older brother and a few school friends followed me, I talked about books some more. Before I ever had a published book or thought I could or had the faintest notion of literary community.

I will always talk about books I love. Celebrating someone’s writing doesn’t make my writing inferior. I feel no threat when I admit someone is a good writer or in my opinion, much better than me. Reading exceptional writing can only make me a better writer (though arguably, so can reading less than remarkable writing).

But maybe my book joy is a selfish act. If I dig deep again, I remember being a pre-teen and watching Steel Magnolias, weeping for want of friends who cared for each other that much. I remember feeling alone and small and scared and unseen. I remember a lack of connection and hunger for community. So, maybe I am selfish for publicly saying nice things about books I love, because when I do, the prospect of bringing the joy of that book to another reader or the author feeling joy because someone sees and appreciates their work makes me happy. Does it make me selfish to feed off the happiness of others?

Maybe.

And maybe I don’t care. I want a world where we all feel a little less starved.

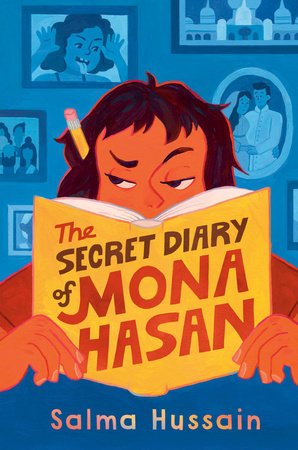

It’s on this note that I welcome Salma Hussain to The (CanL)It Crowd. Salma has been a kindred source of warmth and kindness since I connected with her after reading her funny, smart, and powerful novel, The Secret Diary of Mona Husan, which details a young girl’s move from the UAE to Canada. Mona’s story is one of someone struggling to find themselves between cultures and countries and girlhood and what lies beyond. Mona is also a girl who writes some hilariously bad (but so bad it’s good) pre-pubescent poetry. It’s a story I saw myself in (especially the bad poetry), and it made me feel less invisible.

Here, in this instalment of our series, Salma writes of the balm of finding your people…even though your people won’t be everyone.

Welcome, Salma!

Salma Hussain.

The (CanL)It Crowd with Salma Hussain: Literary Community & Citizenship in #canlit

I love the word ‘citizenship’ that Ghadery has rooted into this conversation about writers’ experiences with building literary community. Citizenship is such a great term in this exchange because the act of creating literary community is truly a give-and-take, labour-of-love endeavour with accompanying rights and responsibilities. Good citizenship is good relationship building.

We create art not just to razzle dazzle and entertain each other but to be in dialogue with each other about concepts and questions. About possible beginnings. And possible endings.

If one is a writer, the tragedy is that after the text has been wrestled onto the page, there is then the obscene but necessary hawking of said art. If the writer has been unfortunate enough to have published something contrarian, out of line with the zeitgeist, work that doesn’t fit neatly within its genre, with a main character from an underrepresented community, with a main character who is sans penis, or any other mix of confounding and delicious deficiencies – the hard work has only just begun.

“Hear ye! Hear ye!” the writer yells into the void. The silence in response can feel deafening.

However, if the writer is lucky (and/or has been advised well), she has put in the hard work of creating a supportive web of interconnectedness with other writers who enthusiastically and good-naturedly join her for the walk of shame around the town square as she peddles her creativity. Such friendships do not merely give her a warm body with whom to pass a winter morning, but rather give her that thing that cannot be generated by herself alone: the hope and good humour to tackle a fresh unblemished canvas without cutting off her ear.

In contrast, if a writer has somehow stumbled upon accolades and attention for their art, then the writing friendships perform the other critical and necessary work of keeping the lucky writer in check (i.e. ever humble and hungry). A writer’s best writer friends help clip the ego when it risks spilling out of their ears and can startle a lauded author with enough tales of rejection and woe such that the celebrated writer dare not be so foolish as to take their success(es) for granted.

Where I am lucky is that I enjoy amplifying the work of others. When I enjoy someone’s art I send a message to say so, or I compose a tweet, write a review, post an Instagram reel, attend a launch, conduct an interview, tell a friend and so forth. When I’ve genuinely enjoyed someone’s work, such effort to amplify feels effortless. The cherry on top is that sometimes this amplification leads to authentic friendships.

Unluckily, it’s certainly happened to me that some friendships have frayed, run their natural course, or I’ve discovered that someone whose writing I’ve supported and/or found interesting, is unfortunately in their villian era, and whenever such a thing comes to pass, it sucks the big one. But looking back upon these experiences, these disasters have also been immensely instructive. These days I welcome the disappointments because it means the astonishments are around the corner. It would be madness to refrain from doing that which brings me joy because the sweet doesn’t come without the sour, and such is the trade-off for our time here above ground: “this being human is a guest house / [and] every morning a new arrival.” Nothing is ever wasted in the endeavour to connect with one another. You win some, you lose some, but you always, always forge ahead.

More About Salma:

Salma Hussain writes poetry and prose. Her fiction has recently appeared or is forthcoming in Fiddlehead, The Humber Literary Review, Temz Review, Queens Quarterly, CV2, The Antigonish Review, The Hong Kong Review, Ex- Puritan and Pleiades: Literature in Context. Her young adult novel, The Secret Diary of Mona Hasan, about a young girl’s immigration and menstruation journey, was published by Penguin Random House in 2022. It was selected for ALA’s Rise: A Feminist Book Project List and shortlisted for the Geoffrey Wilson Historical Fiction prize. A chapbook of poems from Baseline Press is in the works for summer 2025. Befriend her on Instagram and Twitter: @salma_h_writes

About The Secret Diary of Mona Hasan:

Mona Hasan is a young Muslim girl growing up in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, when the first Gulf War breaks out in 1991. The war isn't what she expects — "We didn’t even get any days off school! Just my luck" — especially when the ground offensive is over so quickly and her family peels the masking tape off their windows. Her parents, however, fear there is no peace in the region, and it sparks a major change in their lives.

Over the course of one year, Mona falls in love, speaks up to protect her younger sister, loses her best friend to the new girl at school, has summer adventures with her cousins in Pakistan, immigrates to Canada, and pursues her ambition to be a feminist and a poet.